2. August – 1. September 2019, Schloss Tarasp, Scuol-Tarasp.

3. August – 1. September 2019, Fundaziun Not Vital, Ardez.

Sal Scarpitta (Text by Not Vital)

From the moment Sal opened his door to me, both of usknew we were friends. Sal not only opened his door, but also his eyes, his arms, his mind & his heart.

His studio on Broadway near Union Square was squeezed be-tween 2 buildings. The face of the red building was a fire escape with no escape. There was no buzzer. The only way to reach Sal’s studio was by shouting from the street. Sal liked shouting. I had just arrived from Europe with 5 books that a friend from Rome had given to me, so I could give them to 5 of his friends in NY. 1 of those books was for Salvatore Scarpitta. “Scarpitta” sounded like a small shoe to me since Caligula means small boot.

I became Sal’s assistant. I had never heard of that profession before. My job was to listen to him. Mostly he spoke in English, but sometimes also in Italian, French, Spanish, Romanian & most often in all of these languages at once. I became a professional story listener. We drank coffee in the morning & coffee with Rum in the late afternoon. For lunch we always had 2 Big Macs with extra fries, 1 for his dog.

Sal’s studio was small. At the center of the studio there was a car & a real assistant worked beneath the car, lying on hisback. I only saw him in the late afternoon when he left the studio. The car’s name was Rajo Jack, which was the name of the 1st African American car racer in the US. Sal’s car had everything a car has, but it was motionless. 2 tiny shoes hung from the steering wheel. “That’s for good luck”, Sal pointed out. He was very superstitious when it came to placing a hat or money on the bed & salt always had to be passed in a veryexact manner.

Sal’s best friend was his dog Vito. Sal had elevated Vito to the highest level a dog could ever reach. Once, during a presidential race in the mid 80s, Sal said that Vito should run forpresident. & Sal meant it. There are many stories about Vito. 1 day Sal tied Vito to the back of his truck while he was buying nails at a hardware store downtown & then he drove back to his apartment on the Upper East Side, forgetting Vito, tied to the back of his truck. Vito would usually sit in the back seat & lick my neck which I hated.

In Sal’s studio there were sleds standing on the floor or hanging from canvases which had a hole in the middle. The canvases Sal used were used on operating tables. I once told Sal that it would be best to lean the sleds against the wall. I think that was the only advice I was ever able to give to Salduring my carrier as his listener. He rewarded me with compliments, saying: “Sei propio bravo, exactly the way they should be, es claro, le mur c’est le fond”. & then he would squeeze my cheeks and say: “Tu che sei più che bello”. Once, I had an exhibition at Ascan Crone Gallery in Hamburg & upon my return, every time I would enter the door on Broadway I was: “Aaaaaaaascan Crrrrooooone”. This went on for weeks. While growing up in L.A., Sal was a tree-sitting champion. He escaped punishment 1 day from his father who was also a sculptor. Sal climbed the tree in front of their house & spent 5 weeks up there. According to Sal, this whole story inspired Italo Calvino’s novel “The Baron in the Trees”. In a way, Sal never really came down from that tree.

& then the races. The time Sal was really intense. Standing on a truck in Pennsylvania, watching his feverous race car 59 inthe dirt. & then the stories. This time even in Latin.

I never met a more profound person than Sal. He was intelli-gently pure, an artist different from all artists I knew or ever met. He never mentioned any names, but when he did they were Franz Kline & Frederick Kiesler, both names starting with F & K. When Sal talked about other artists, politicians, or the human race in general, he would fill up the blank between the 2 letterswith other 2 letters.

He lived in a world which was only his & I am so blessed to have been able to peak through 1 of his many windows & to sometimes even enter Sal’s world.

Not Vital, July 2019

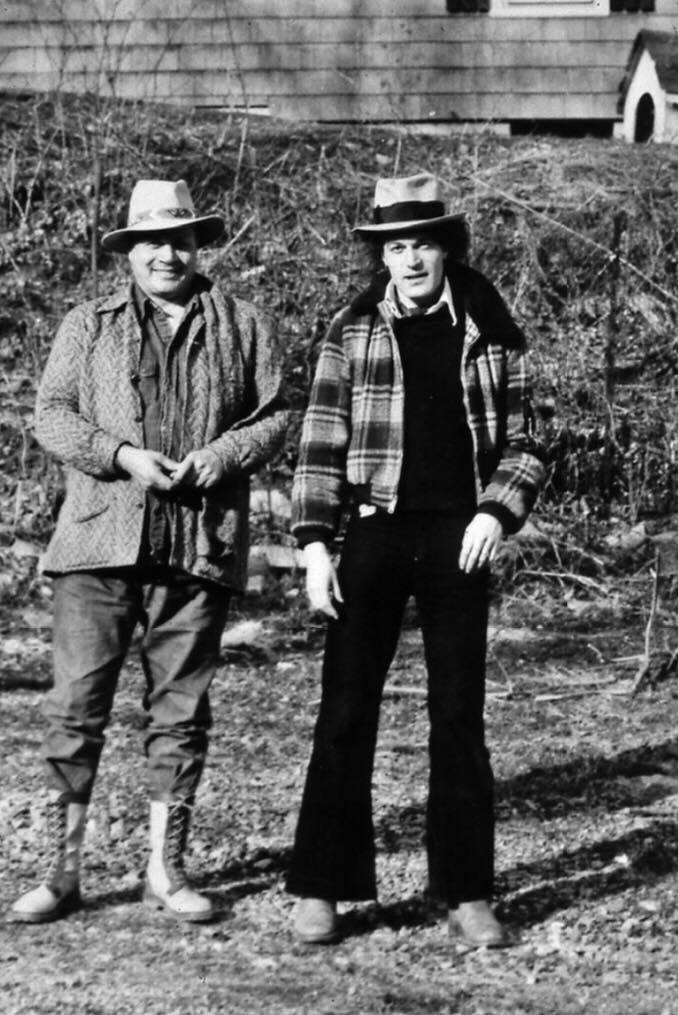

Newport, Rhode Island, 1977

Courtesy Richard Milazzo Archives, New York

DREAM MACHINES (Text by Giorgia von Albertini)

DREAM MACHINES brings together the work of Salvatore Scarpitta (1919–2007) and Panamarenko (1940) for the first time. Scarpitta and Panamrenko were both idiosyncratic, freedom-loving artists with a deep fascination for machines and vehicles. Independently from each other, they worked with a variety of non-traditional materials such as bandages, metal, rubber, magnets, engines and wood, to create art-works that are hybrids of technology and flesh, performance and emotion.

Scarpitta’s life-long obsession with racing cars led to sculptures made out of found materials or car parts and even the fabrication of entire racing cars. While often non-functional metaphors displayed in the exhibition setting, some of Scarpitta’s cars were actually fully operative and driven by both racing drivers and himself in official dirt-track races in the United States. These cars and the objects related to them a realways impressive in color and shape, suggesting to theviewer a distinct feel of speed and adventure. While Scarpitta re-constructed machines, Panamarenko is bestknown for inventing them. His constructions often allow us to feel what it would be like to perform actions that conventional wisdom dismisses as impossible, or, at best, imaginary, for instance flying like a fruit fly, braving the sea trapped in a small submarine waterbike or being shuttled between steadily orbiting electromagnetic cigar-shaped space stations in curious versions of flying saucers.1

Interestingly, while both of these artists devoted themselves largely to machinery and technology in practices that engaged with futurism, their work does not feel cold, scientific or even macho. On the contrary, it is full of affect, imbued with dreams and vulnerabilities and a serious preoccupation with history and the human condition.

Scarpitta was born in New York in 1919. His mother was an actress of Russian-Polish descent and his father Italian sculptor who had migrated to the United States in the first decade of the 1900s. Shortly after Scarpitta’s birth, his family moved to Los Angeles. Growing up in Hollywood, Scarpitta was able to cultivate his passion for car racing and immerse himself in the attendant universe. At the Legion Ascot Speedway in BoyleHeights he would watch races and meet glorious drivers such as Frank Lockhart and Ernie Triplett, who held an extraordinary, enduring fascination for him.

At age seventeen, Scarpitta decided to explore his Italian heritage and moved to Italy to study in Rome. Then, during WorldWar II, he took part in the Italian Resistance as a liaison with the American army, after which he enrolled in the US Navy. Following his discharge in the spring of 1946 in California, he returned to Italy and settled in Rome.2

At that time, after the war and in the early 1950s, Italy was undergoing a period of profound artistic renewal. Artists like Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, Pino Pascali and Piero Manzoni generated a climate of extraordinary energy. It is in this context that Scarpitta began to create his bandage paintings and the first relief canvases. While the former works seem a direct consequence of the experiences and the aftermath of the war, as if bandaging battle wounds, the latter are more oblique: the canvases, some painted, some almost raw, conceal a corrugated metal core that creates irregularities and depressions on the surface.3 With their visceral surfaces, these early works evoke both vulnerability and healing, decay and persistence. Upon returning to New York in 1958, Scarpitta, now showing with Leo Castelli, started a series of works marked by anX-structure (1959–1961). Notably, the recurrent X of this periodis not only a structural element, but also an intersection, that is, a location of potential collision or change of direction.4And indeed, in the beginning of the 1960s, Scarpitta abandoned abstraction and returned to the memories and fascinations of his childhood. He used found materials and fragments of racing cars to build sculptures (1962–1964) and fabricated entire racing cars (1965–1991) at his studio on 333 Park Armory South.5 The first car, Rajo Jack, was dedicated to one of the earliest black race car drivers, who was banned from the racesin the 1920s because of his color.6

Scarpitta not only built racing cars and had a racing team of his own, he also made numerous highly expressive drawings

that suggest the swooping physicality and intensity of racing. Often working with ink on paper, he froze the racer’s rapidlyshifting view, while rendering the buzz and tension of the race palpable through speedily executed lines and a simultaneity of perspective.

Included in DREAM MACHINES is Doug (1989), a drawing of a racer fiercely staring through his visor. While the driver’s faceand helmet are executed in precise detail, with an inscription on the helmet reading “DOUG”, the highly gestural rendition ofthe driver’s torso and hands is nearly abstract, indicating quick movement and leaving it to the viewer to decide whether the driver is still holding the steering-wheel or already takingoff his gloves.

KARS 59 (1989) is a portfolio of three etchings dedicated to Scarpitta’s Sprint Car number 59, the winning car on the Williams Groove Speedway, driven by Bobby Essik on April 14, 1989. The day after this seminal victory, Scarpitta made three etchings, each depicting a specific moment in the race: the nearly paralyzing tension before the race, the disintegrating madnessof the race, and the cathartic moment of victory.

DREAM MACHINES also includes five videos that Scarpittamade in collaboration with his former student and partner Joan Bankemper. These historical documents visualize the reality of racing as well as Scarpitta’s understanding of the race as an art form: Sal is Racer (1983–84), Racer’s Tattoo (1985), Potato Masher (1985), Message to Leo (1986), and Crash (1990). A series of prints pulled from the first video, Sal is Racer, depicts Scarpitta racing himself – a rare document that taps into the power and trauma of Scarpitta’s epic journey and testifies to the fact that this artist truly lived for the race. Indeed, the race itself, with all of its ups and downs, victories and defeats, was a quintessential part of Scarpitta’s oeuvre. Under- stood by the artist to be a journey of spiritual metamorphosis, the deeply and seriously lived world of the race extended Scarpitta’s practice into the fields of performance and happenings.

After a decade devoted largely to constructing and reconstructing racing cars, Scarpitta began to make sleds almost always using only found materials: skis, hockey sticks, rungs, bandages, chair backs, and wood. Bound, laced and tiedtogether with cotton strips and thongs, then coated with resins, rubber, tar, coffee, or wax, these constructions take anarchaic turn reminiscent of Native American or Nordic sleds.7

At a far remove from the repetitive circularity and speed of therace track, the sleds become ritual objects that open upavenues to what might be called a nomadic or transcendental odyssey; they convey the physical and spiritual trials of anarchaic passage through the vast silence of an empty landscape.8

While most of Scarpitta’s sleds incorporate organic materials and evidence of handicraft, Parachute Sled (1986), included in this exhibition, is a hybrid work on the threshold between archaic handicraft and futuristic machine. It is a traditional, free-standing wooden sled, but with a bright blue fiber-glass para-chute strapped to it. By conjoining these disparate elements,Scarpitta has created a sculpture that speaks both to our age- old heritage, as well as to men’s modern desire for freedomand his compulsion for take-off. What would an archeologist ofthe future say on finding this artefact?

Born roughly two decades after Scarpitta, Panamarenko made his appearance as a self-proclaimed “multimillionaire”, who was the driving force behind playful street performances or happenings, orchestrated in the mid-1960s in central Antwerp by a small group of young artists.9 During this time he conducted his first technical experiment: the construction of magnetic shoes that enabled him to hang from a steel ceiling and walkabout on it during a performance in Brussels in 1967. 10

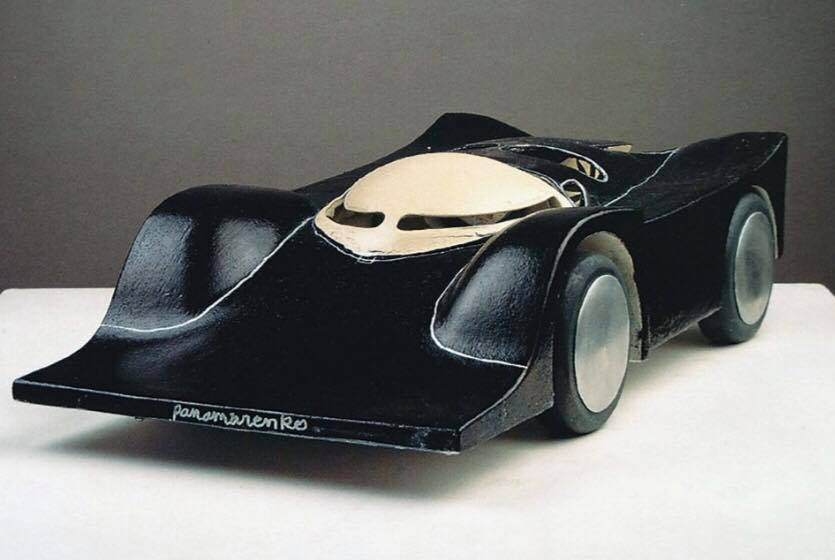

That same year, while revisiting childhood memories, Panamarenko built Prova Car (1967), a work that embodies a striking contradiction: the streamlined design gives it a futuristic feel, but any illusion of functionality is expertly undermined by the casual execution and non-standard choice of materials. To Panamarenko it “symbolizes the music of racing cars on the track”. 11

Polistes-car, 1990

Iron, polyurethane rubber, cellophane and aluminum13 × 50.5 × 26 cm

Courtesy Deweer Gallery, Otegem, Belgium

In 1975, Panamarenko published a small blue artist book, in which he presented his research into the concepts of gravity, forward motion, insect flight, jet propulsion and rotor lift.12

In this early document, the seeds of virtually all the objects thateventually followed were sown: flying machines, automobiles,spacecraft, ships, and lastly mechanical robots.

Panamarenko’s venture into the construction of flying machines began with his first airship, The Aereomodeller (1969–1971).13

This dirigible airship was 27 meters long and consisted of a cigar-shaped balloon, propelled by two aircraft engines, andwith a basket-like gondola attached to it. It was mobile home which was meant to travel around freely. Panamarenko wantedto fly from Belgium to a festival in the Netherlands to test the airworthiness of this fantastic construction but the Dutch aviation authorities sent a telegram to the artist, banning the flight.14 The Aeromodeller has since become the most iconicwork in Panamarenko’s oeuvre. In the decades that followed the first version, the artist built numerous variations and proto-types of airships, each different in form, color and proportion. Included in DREAM MACHINES is a small model for such an airship, entitled Panama: Aereomodeller I (1984). Made ofmetal, painted cellophane, thread, wood, plastic propellers andjerry cans, the silver construction is embellished with colorful letters and symbols. Executed in simple materials but with utmost attention to detail, this inert, hand-made object is as cerebral as it is sensual. Most of all, it makes us understandhow much Panamarenko was invested in the production process itself, rather than seeking to prove the validity of histheories or systems.

Towards the late 1960s, Panamarenko showed a growinginterest in flying saucers and their means of propulsion.The following years saw not only the construction of a new spacecraft, but also research into the various possibilities of using existing magnetic fields as cosmic highways by whichflying saucers might traverse the solar system. The artist’sfascination for the cosmos culminated in Ferro Lusto, a project that he described as “a spaceship of 800 meters in length and fit for a crew of 4000”.15 To Panamarenko the Ferro Lusto was the mothership that would carry various smaller crafts named Bings.

Here, Studie Magnetische Proporties 2 (1982) and Bing of the Ferro Lusto (2002) exemplify the work that resulted fromPanamarenko’s enduring fascination with the cosmos. The for-mer is a drawing of a so-called Bing, made while studyingmagnetic fields. The latter is a sculpture, a three-dimensionalBing made of epoxy, resin, electric motors and metal, whichresembles a round hat, standing on four slender metal sticks.The sculpture’s body is rendered in white and light brown hues, its surface smooth and delicate as skin. A saucer-likespace hidden underneath the sculpture’s round brim isdesigned to transport passengers. Unmistakably technical yetutterly fragile and elegant, this construction eludes art historical classification: is it a machine, a model, or a poetic sculpture of unique formal beauty?

Because Panamarenko was constantly thinking and re-thinking, trying and re-trying, calculating and re-calculating his con- cepts, he produced a large body of studies and drawings relatedto his different projects. While Rug Umbilly (1984) and Buzz- Zoom (2005) demonstrate the artist’s interest in the mechanical duplication of insect wings, Persis Clambatta (2001) andCocotaxi (2003) are indicative of the last chapter in Panama- renko’s oeuvre: servo-robotica. Studying archeological ac- counts of prehistoric fossils of Archaeopteryx birds as well as live chickens on the Furka Pass in the Swiss Alps, Panamarenko worked on different versions of servo-robots that looked,moved, and flapped their wings like birds.16

Then, in 2005, at the age of 65, Panamarenko announced that he had had enough and was going to retire.17 Some time beforethat, he had stated: “If you make a truly functioning robot, then I think you’d pretty quickly say: I’ll make my own coffee!” 18 Allegedly, that is precisely what Panamarenko is doing now.

Scarpitta and Panamarenko were singular artists who pursued a radical and total vision. While their practices both touch upon the modernist project of the symbiosis or hierogamy of humans and machines, and their oeuvres both entail elements of happenings and performance art, their sources are not so much to be found in an art-historical matrix, but rather in their respective childhood memories and their deepfascination with machines and vehicles. Working with un-orthodox and often simple materials, they constructed machi- nes that frequently lacked the decisive elements for func-tionality. They are thus not simply vehicles of transportation, but rather vehicles of transformation.

Today, in the digital age, the works of these two artists are infused with a certain nostalgia or melancholy. Harboring the human touch and charged with symbolic character, their three-dimensional constructions transcend the status of art, becoming artifacts of human action and history that teach

us the importance of the imaginary and the imagination.

Giorgia von Albertini, July 2019

Art Basel Salon Talk 2016 :

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=ZdL4VZMm_ig